↧

Photo of the Week

↧

Taking Stock: Vanier’s Built Heritage

A cluster of homes on Emond Street (1910 to 1925)

In her 1961 classic, The Death and Life of American Cities, Jane Jacobs writes of four conditions deemed necessary for the creation of vibrant neighbourhoods. In addition to there being population density, mixed-use and short blocks, Jacobs points to the value of mixed age buildings, suggesting that “the district must mingle buildings that vary in age and condition” (1961, p 150). As shown in the images below – and in a theme we hope to build on at VanierNow over the coming year – Vanier fares well on this last characteristic, with a building stock built over a period of 140 years. One finds 1870s workers housing (73 Barrette is estimated to have been built in 1871), hundred-year old churches such as St Margaret’s (constructed in 1887-88, with a cornerstone laid by Lady MacDonald) and St Charles (dating to 1908), 1950s post-war housing construction and contemporary, modern design. Today, our neighbourhood includes buildings from various periods – each offering a glimpse of Vanier’s past.

And yet, a review of today’s City of Ottawa Heritage Register shows only two Vanier properties: Richelieu Park (300-310 des Pères Blancs) and Gamman House (306 Cyr Avenue). The Register, guided by the Ontario Heritage Act, is intended to facilitate management of the physical heritage of properties or heritage conservation districts, prohibiting alteration of designated properties without Council’s approval. Vanier’s first property to be designated was (and is) Richelieu Park, enacted through a by-law by the former City of Vanier in 1996. Designated portions of the park include the library building, the Statue of Mary and landscaped circle around it, the entrance posts and wrought iron fence, the maple stand and the tree-lined boulevard along des Pères Blancs Avenue.

Vanier’s second property, Gamman House, was designated in March 2004 by the new City of Ottawa – but also owes its preservation to the former Vanier City Council who negotiated with Vanier’s Club 60 (a social club for seniors) in the mid-1990s to ensure the small Victorian house was preserved. Negotiations then reflected the tenor of discussions by the Vanier Planning Advisory Committee, oriented away from assigning formal heritage designations (fearful of the limitations they would impose on owners) and towards pursuing a voluntary approach.

While formal designations may be only one mechanism for acknowledging the value of built heritage, the presence of only two designated properties belies the significance of many properties in Vanier today. And the exclusion of significant references to Vanier in citywide publications of Ottawa’s built heritage, such as Kalman and Roaf’s 1983 publication Exploring Ottawa or the City of Ottawa’s Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee’s 2000 publication Ottawa: A Guide to Heritage Structures, further contributes to this paucity. The images below demonstrate Vanier’s rich architectural history; so, how might we foster a stronger awareness of this presence? And, during this time of (welcomed) wide-scale renewal and reinvestment, how might we also ensure the celebration and continued recognition of our built heritage?

One start may be to look again to Vanier`s past. Similar questions were asked in September 1994, when Vanier City Council passed amendments to the City`s Official Plan, including new heritage preservation policies and a plan to embark upon research of Vanier`s heritage buildings, particularly those built before 1920. Background material prepared in January, 1995, pointed to a development pattern dating back to 1875 that was still recognizable in the 1990s (and indeed, today), particularly in and around Janeville, on streets including Savard, Cyr, Hannah, Montgomery, Selkirk and Palace. Developments in Clarkstown, on streets such as Barrette, soon followed. Discussion even pointed to the strong potential for recognizing Palace, Emond and Barrette Streets as heritage districts, noting that between 233 and 257 Emond alone, six buildings dating from between 1910 and 1925 were still standing (City of Vanier, 1995).

Residents today are still able to see the results of efforts launched then – evident in the red plaques today on properties across Vanier. The plaque program, then named as an Award of Excellence, was created in 1996 by the Vanier Heritage Committee in cooperation with Vanier City Council and Action Vanier. The annual award, intended “for the conservation of building heritage,” recognized specific buildings – and though not designating properties under the Ontario Heritage Act, included the red plaques. Awards were given in various categories, including restoration, renovation and reuse, recognizing property owners who fix up, preserve or maintain properties, including even the simple wooden structures that had too frequently been lost through fire or neglect.

A review of just one year’s award recipients provides an illustration of Vanier`s architectural mix. In 1999, the 1936 Art Deco home at 235 Tudor was honoured alongside a 1905 brick home at 241 Marier (with an original tin ceiling restored inside) and an 1890 clapboard home at 107 Selkirk (Campbell 1999). A year later, recognition was awarded for a 1950 post-war bungalow on Dollard (Young 2000). The awards ran from 1997 to 2001.

As Vanier is now situated within the City of Ottawa, one possibility for future recognition of Vanier’s heritage could be to encourage nominations through the Ottawa Architectural Conservation Awards, an annual City awards program recognizing outstanding achievements in heritage conservation. Another option, of course, is to pursue designation of additional properties, through the Ontario Heritage Act, to be added to the City`s Register. This option will necessitate working through and earning the support of the (newly forming) Built Heritage Sub-Committee of the City’s Planning Committee.

While attention may be warranted to numerous buildings that are currently undesignated, one particular property frequently features in discussion – namely, the St Charles church on Beechwood Avenue. Dating to 1908, the church has been a Vanier landmark, where Father François-Xavier Barrette served as priest from 1912-1961. As Yanick Labossiere, a researcher at Muséoparc, notes (translation), “This church is much more than just bricks, it is the memory of a people which has long fought for its survival.… I believe it is possible to develop a project that could save the building, that is to say, the church and its rectory….” (Labossiere, 2011). Labossiere’s final words might apply to numerous other buildings in Vanier, too. “Let us fight for our heritage; it is our legacy that is at stake.”

(Mike Bulthuis)

73 Barrette Street: a much altered, and perhaps oldest, building in Vanier (1871?)

Saint-Charles Church (decommissioned in 2010), Beechwood Avenue; by architect Charles Brodeur (1908)

![]()

,+307+Montgomery+Street.jpg)

Former Eastview Public School (now École secondaire publique L'Alternative), 307 Montgomery Street (1910)

![]()

Former Eastview Roman Catholic School and Vanier City Hall (now Les Lofts du Montfort); by architect Francis Conroy Sullivan (1912)

![]()

Historical gate post (1940s?) and statue of Our Lady of Africa (1955), part of the former White Fathers’ seminary (now Richelieu Park)

![]()

Vanier Community Church (formerly City Church, originally built as La Paroisse Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit), 155 Carillon Street (1958)

![]()

Mid-century modern home (with massive chimney wall), 160 Duford Street (corner of Lavergne) (1950/60)

![]()

,+140+Duford+Street.jpg)

Wabano Centre (under construction), by Douglas Cardinal and Cardinal Conley & Associates Inc. (2013)

(Photographic study by Mike Steinhauer)

Sources:

Campbell, Jennifer (1999) “Preserving Vanier's past: Heritage Awards honour top renovations, restorations” Ottawa Citizen, February 13, p. H1.

Jacobs, Jane (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books)

Labossière, Yanick (2011) “L’histoire de St-Charles: Éditorial” L’Artefact (Vanier: Museoparc), September.

Vanier, City of (1995) Memo to Vanier Planning Advisory Committee, Re: File PD 2.4.10 Report on Heritage Buildings in Vanier. From Donald Morse, January 23.

Young, Kathryn (2000) “Simple, but good: Vanier celebrates the past with heritage awards” Ottawa Citizen, February 18, p. H1.

(Photographic study by Mike Steinhauer)

Sources:

Campbell, Jennifer (1999) “Preserving Vanier's past: Heritage Awards honour top renovations, restorations” Ottawa Citizen, February 13, p. H1.

Jacobs, Jane (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books)

Labossière, Yanick (2011) “L’histoire de St-Charles: Éditorial” L’Artefact (Vanier: Museoparc), September.

Vanier, City of (1995) Memo to Vanier Planning Advisory Committee, Re: File PD 2.4.10 Report on Heritage Buildings in Vanier. From Donald Morse, January 23.

Young, Kathryn (2000) “Simple, but good: Vanier celebrates the past with heritage awards” Ottawa Citizen, February 18, p. H1.

↧

↧

Montreal Road: Architectural Snapshots (of what was and what was meant to be)

Here in Ottawa, this week is Architecture Week, with a festival of talks, tours and films (even a pub crawl) organized by the Ottawa Regional Society of Architects – all oriented to the celebration and study of the discipline of design. In the spirit of this festival, and having introduced components of Vanier’s built heritage last week, we’re shining some light on a number of buildings that once existed, or designs that were once proposed, along Vanier’s Montreal Road corridor.

To begin, we point to the clean lines of the 1950 addition of the Eastview Hotel – a prominent landmark at the corner of Montreal and Cody for 30 years. The hotel stood opposite the St. Margaret’s Anglican Church until a fire destroyed both the 30-room addition and the original structure, dating from 1900 (ALSO: Unlikely Neighbours). Today, the site is occupied by a City of Ottawa ambulance depot.

Photo: Postcard by Folkard, Montreal (1950s)

↧

Vanier’s Omnicentre: An earlier vision for Montreal Road

Conceptual drawing of Phase One of the Omnicentre (more renderings below; click to enlarge)

In 1976, in response to challenges “to combat stereotyped urban development patterns favouring suburban shopping centres [and] concentrated commercial complexes in the core of Ottawa” (1976: 9), the City of Vanier launched plans to develop a renewed commercial core on Montreal Road to be anchored by the Vanier Omnicentre. Conceptual plans and drawings for Phase One and Two were completed in 1976 by Craig and Kohler, Architects, the same firm that designed Ottawa's Civic Centre at Landsdowne Park. The multi-use commercial complex was to be situated at the corner of Montreal Road and the Vanier Parkway.

Plans would involve clearing a three-block parcel of all buildings and structures, relocating residential tenants as required, and building a two-level underground parking facility. Phase One would hold Vanier¹s City Hall, complemented by shopping areas, office towers and a 200-room hotel with convention facilities. Phase Two would include four apartment buildings (connected by landscaped courtyards), an enlarged shopping area, a third office tower and a landscaped square around St. Margaret's Anglican Church.

Map of Vanier showing Omnicentre along Montreal Road and Vanier Parkway (click to enlarge)

Intended to stimulate development activity by the private sector on adjacent properties, funding for the Omnicentre itself was sought from the provincial Ministry of Housing¹s Downtown Revitalization Program. The entire project, comparable in size to one of the many federal complexes in Hull, may have had the opposite effect: the long-term plans called for the removal of Savard, Cyr and a portion of Cody Avenue, and the demolition of the Eastview Hotel, Gammon House and the Legion. In return, this complex, in the style of Phase IV of Place du Portage, would have changed the three narrow blocks (and subsequently the entire neighbourhood) beyond recognition.

Conceptual drawings of underground parking facility, ground floor building and landscape design and longitudinal rendering (click to enlarge):

Sources:

Drawings: Vanier, City of (1976) NIP Redevelopment Plan 1976, NIP Redevelopment

Area, Downtown Revitalization Plan (A Redevelopment Plan), Detailed

Development Scheme No. B1. October.

Map: VanierNow 2012; based on conceptual drawing found in NIP Redevelopment Plan and aerial photograph from Bing Maps (2012 Microsoft Corporation; Image by 3Di; 2012 Nokia; Accessed September 2012: http://www.bing.com/maps/)

↧

A Modernist Gem on Montreal Road

In our final post during Architecture Week, we look to one last building on Montreal Road – this one having been constructed in the mid-20th century and still standing today. The late 1940s and 1950s were years of significant growth for Vanier (then Eastview). Bus service was improved, Montreal Road was widened, a modern new high school was constructed, and hundreds of families moved into modern apartment buildings and new homes (see also: Blake Boulevard: the 1950s housing boom revisited). To keep up with this growth, the Bell Telephone Company purchased the site of the École Ducharme in 1949 to build a “dial central office” for Ottawa East. The former school, only constructed in 1941, had burned down in March, 1949.

The Bell building, located at the corner of Montreal Road and Olmstead, was designed by Hazelgrove and Lithwick. The flat roof, clean horizontal lines and prefabricated concrete curtain wall are key traits of the International Style. The architectural firm also designed the Sir Charles Tupper Building on Riverside Drive, the Spanish Embassy on Stanley Avenue, and the (soon to be demolished) Beth Shalom congregation on Chapel Street.

Sources:

“Bell Telephone Buys New Site in Eastview.” The Ottawa Citizen. July 6, 1949. Page 23.

Benali, Kenza. Parent, Jean-François. “Vanier : bastion francophone en Ontario.” Encyclopédie du patrimoine culturel de l'Amérique française. 2007. Accessed September 25, 2012. (link)

Bergero, Claude. Index des périodiques d'architecture Canadiens, 1940-1980. Quebec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 1986.

Laporte, Luc. Vanier. Ottawa: Centre franco-ontarien de resources pédagogiques, 1983.

“Rapidly Growing Eastview; Capital’s Eastern Gateway.” The Ottawa Citizen. September 17, 1949. Page 16.

Top image by VanierNow, 2011.

↧

↧

For Lease: Space Available

Clockwise from top left: (1) public map of DownStreet Art locations; (2) street signage; (3) “Beyond the Blue Mountains,” film by Mollie Davies, Artery Gallery; (4) entrance to William Oberst Studio; (5) pavement markings (All Images: VanierNow, 2012)

Exploring the old commercial hub of North Adams, Massachusetts, earlier this summer, it was hard not to draw certain inspiration. In the core of this former industrial city and mill town, set in the Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts, we were able to view Jarvis Rockwell’s toy installation (below), experimental film and activist art used in the Occupy Movement, and see a working traditional letterpress (run collectively) – all for free – all in former commercial mainstreet storefronts that had gone vacant when industry left.

The arts exhibits are all part of DownStreet Art (DSA), a public art initiative, founded in 2008, that is today transforming downtown North Adams. Today, DSA brings visual and performing arts, exhibitions, film screenings and site-specific installations to this old downtown. And the town’s vacant commercial storefronts have served as host sites for many of the temporary (or, pop-up) summer galleries, all with the permission of property owners – with some becoming converted into permanent gallery spaces. To be sure, the festival is aided by the presence in town of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), which was established in 1999 in the sprawling site of the former Arnold Print Works, a major producer of printed textiles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But the local flavour of DSA stands apart from MASS MoCA, too.

The initiative is a program of the Berkshire Cultural Resource Center, a non-profit organization run through the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, today providing professional development and support to artists and arts professional – and building a local creative economy. In North Adams, local business owner Keith Bona explains, DownStreet Art is “making empty store fronts and bland walls attractive and inviting.”

Toy pyramid installation by Jarvis Rockwell, Jarvis Rockwell Gallery (Image: VanierNow, 2012)

It goes without saying that today’s vacant storefronts and spaces on Montreal Road and Beechwood Avenue present opportunities. So, are there property owners interested in working with community partners to find creative reuse of these vacant spaces – even for a short time? The North Adams experience suggests that even temporary uses of space have enabled the community to experiment with new ideas, instil local confidence, promote local economic development and draw others to town. There are other examples, too. The Made in Sterling shop, in Stirling, UK, aims to showcase the work of local artists in a vacant storefront on the traditional highstreet. In a more suburban setting, the Service Center for Contemporary Culture and Community, established in an abandoned tire shop in Indianapolis, has created space for community-driven arts, fitness and skills development spaces.

So, as a community, what visions might we have for our traditional mainstreets? Spaces for the arts or film screenings? A used bookshop? A community-driven pop-up café? A space for training and development? A single space that might flexibly enable all of the above? How might we make possible the reuse of vacant space – even one storefront at a time?

(Mike Bulthuis)

↧

Photo of the Week

↧

Inspired by the Past? A November forum invites ideas on Vanier’s future

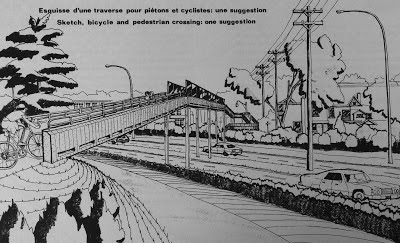

Sketch, bicycle and pedestrian crossing [over the Vanier Parkway]: one suggestion

(click to enlarge) (Source: City of Vanier (1976) NIP Redevelopment Plan, p 104)

Though not a particularly fanciful design (the aesthetic of mid roadway posts or the practicality of stairs on one end are peculiar…), the 1976 suggestion for an “elevated walkway and bicycle crossing” to span the Vanier Parkway may have been too fanciful an idea. The crossing was to connect residents living east of the roadway with the riverfront parkland and open space along the Rideau River.

Indeed, the suggestion was not a top-level priority, but it was one of many that arose through the Neighbourhood Improvement Program project in Vanier (led by the Citizens Committee Executive, whose photo we showed here). Other recommendations included the development of the “White Fathers Property” into today’s Richelieu Park, and the improvement of street lighting and sidewalks – many suggestions that were subsequently implemented through the joint efforts of residents and the City. On November 3, 2012, through a local Community Forum, the City of Ottawa is again partnering with Vanier and soliciting input towards determining our neighbourhood’s future.

These initiatives can be productive exercises. The City of Vanier introduced further community improvement policies in the mid-1980s and again launched neighbourhood planning in the mid-1990s, distributing bilingual, two-page questionnaires to households and businesses in particular areas. Whether thinking of stylized lampposts on Montreal Road or brick-laid crosswalks at McArthur and the Vanier Parkway, many community amenities or characteristics we enjoy today arose from earlier processes of community engagement.

The November Forum is being spearheaded by the City’s new Neighbourhood Connection Office (NCO), created earlier this year to support neighbourhoods with needs assessments, priority setting and project implementation. The Forum, open to all residents and merchants (and free of charge) offers two significant opportunities. First, the Forum presents a chance to dialogue with other community members about the priorities we imagine for our neighbourhood, whether related to transportation, parks, local development, arts and culture or other top-of-mind issues. Do we need to slow down traffic or improve our parks? What would it take to enhance cycling safety? Later this week, applications are expected to open for the NCO’s Better Neighbourhoods Program; what ideas might we have to make Vanier a better neighbourhood?

Second, senior City staff will offer presentations and answer questions on City initiatives that may have impacts on and implications for Vanier, ranging from cycling infrastructure and cultural mapping to the imminent review of the City’s Official Plan and Transportation Master Plan (among other planning tools). How might our suggestions under these citywide initiatives help to create a more liveable community, or one better planned for pedestrians? Or, how might revisions to Vanier’s Site Specific Policy– a component of the City’s Official Plan – make Montreal Road more into the kind of main street that we aspire for it to be?

Where will this go? That’s partially up to us – long-time, current and new members of the community – to decide.

(Mike Bulthuis)

Source:

City of Vanier (1976) NIP Redevelopment Plan, 1976. NIP Redevelopment area.

↧

Photo of the Week

↧

↧

MacKay, meet Barrette: renewing Beechwood for today’s community

Beechwood Avenue, late 1980s: Foreground: Art Gallery, 86 Beechwood; Background: El Meson, 94 Beechwood (Source: Heritage Canada Foundation, 1988).

Reports last week of Minto’s imminent purchase of the burned-out property on Beechwood’s west end, coupled with a second community forum organized for Monday evening (October 29) by the Beechwood Village Alliance, bring encouraging news for another of Vanier’s commercial main streets. In response, Le Droit’s Jonathan Blouin writes of “hope” for the area while the Ottawa Citizen’s Joanne Chianello suggests “the nightmare” for Beechwood may soon be over. Indeed, coupled with Domicile’s redevelopment of Kavanaugh’s Esso at 222 Beechwood into The Kavanaugh (scheduled for construction in 2013), the street may be ripe for a new beginning. Beyond its physical change, the positioning and imagining of Beechwood as a boundary between communities – dividing north and south – may be falling away.

The vitality of neighbourhood main streets is often cyclical, and Beechwood has undoubtedly had better days. The post-war opening of the Linden Theatre at Crichton and Beechwood, then to become the Towne Cinema, served as a neighbourhood destination. The cinema’s closing in 1989 (as co-owner Bruce White opened today’s Bytowne Cinema on Rideau) brought Mountain Equipment Coop to the street for ten years, before its closure in 2000. Smaller establishments elsewhere on Beechwood have similarly come and gone.

Linden Theatre (1947), Beechwood Avenue (Source: Archives of Ontario, AO2866, via Miguelez 2004)

Beechwood’s past successes have perhaps been all the more remarkable arising from its split identity – and the numerous players that have had responsibility for its well-being. Until amalgamation in 2001, the street divided the City of Ottawa (the north side) from the City of Vanier (the south side), with a small portion also marking the edge of the Village of Rockcliffe Park. As a result, Vanier’s efforts at renewal through the 1985 creation of a Business Improvement Area (BIA), for example, included only properties on the south side. Still today, one finds decorative lampposts only along Beechwood’s southern sidewalk -- installed by the BIA in the late 1980s. A set of commercial development guidelines, published by the City of Vanier in 1991, similarly only refers to strategies for the south side – with properties on the north grayed out (the Report highlighted various commercial establishments that had arrived in the 1980s, including an art gallery at 86 Beechwood, shown above, just to the west of El Meson).

Mapping Beechwood's commercial properties (Source: City of Vanier, 1991)

The challenges imposed by this “Beechwood as boundary” narrative were long-standing. The cities of Ottawa and Vanier struggled to negotiate cost-sharing agreements for sewers and road construction in the 1960s. Even much earlier, the intended allocation of local tax dollars to local services (within a local jurisdiction) was challenging. Already in 1923, difficulties arose when parishioners of St Charles Church, located on the Eastview (Vanier) side of Beechwood, were sending their children to a Separate School in nearby Ottawa, a situation that drove the Ontario legislature to establish a local school board – independent from both the Eastview and Ottawa school systems – to ensure tax revenue was directed appropriately (Shea 1965).

Both municipal amalgamation in 2001 and this year’s expansion of the Vanier BIA (to include properties on both sides of Beechwood, see earlier post) have helped to dismantle these jurisdictional challenges. Already in the 2006 Beechwood Community Design Plan, one reads that “Beechwood Avenue, in its entirety, is a mainstreet that serves as the local shopping area and the central meeting place for a diverse group of surrounding neighbourhoods, [and] it makes sense from a marketing and business perspective that the street be seen as a single unit with a design that is consistent and reflects this diversity of uses” (CDP 2006).

Even so, the street may still mark a boundary – between neighbourhoods (New Edinburgh, Lindenlea, Rockcliffe Park and Vanier) and municipal wards. So, this period of renewal on Beechwood may also offer an opportunity to dismantle boundaries that may have become engrained in the imaginations of many residents – boundaries that may have divided communities to the north and south. To the north of Beechwood, one celebrates the legacy of Thomas MacKay, the father of New Edinburgh, who subdivided the land and created a community in the late 1800s. To the south, one thinks of the old village of Clarkstown and the legacy of Father Francois Xavier-Barrette, priest at St Charles from 1912 to 1961, and an individual credited with the promotion of the neighbourhood’s French character. Alongside stories on Beechwood’s north side of the Linden Theatre and high-end auto sales (seen in this 1955 ad), the south side, particularly towards the river, may have been known more for iron and metal yards, scrap metal storage and the Dominion Bridge Company along the former railway tracks.

These local neighbourhood stories are real, and the telling and celebration of each is not only important, but offers a sense of place to communities and their residents today. At the same time, it is important to consider the significance of Beechwood as a main street (along with interests in its renewal), within each of these neighbourhood’s stories. In today’s discussion of Beechwood, it is perhaps intriguing that the street is frequently positioned as a hub within the New Edinburgh community (see recent enRoute article). The desire for shops and services that meet residents’ needs and interests must equally come from communities both north and south. And while Heritage Conservation Districts to the north may either border on Beechwood or lay around the corner, the street’s proximity to Barrette (with its many properties currently included on the City’s Heritage Reference List) – and the heritage value of various properties actually on Beechwood’s south side (e.g., St. Charles Church and El Meson) – equally compels attention.

Heritage Buildings on and near Beechwood (Source: Beechwood Community Design Plan, 2006)

Perhaps new stories, and new imaginations, of Beechwood are being written. Renewal will serve the entire community and the neighbourhoods within – New Edinburgh, Vanier, Lindenlea and Rockcliffe Park. The banner that hung on the wooden wall surrounding the fire site in late August, reading “Our Community Needs You to Build Something – Now” says it best. Each of our communities needs to work together – for our shared community’s future. See you at the meeting Monday night.

(Mike Bulthuis)

Sources:

Miguelez, Alain (2004) A Theatre Near You: 150 years of going to the show in Ottawa-Gatineau (Ottawa: Penumbra Press)

Ottawa Citizen (1989) “Vanier: Two streets to get decorative lighting” August 25. Page C3.

Ottawa Citizen (1985) “Vanier designates business improvement area” October 16. Page C2.

Shea, Philip (1965) History of Eastview (Ottawa) Unpublished. Compiled at Carleton 1965, under the direction of Historian, N.C.C. September 10, 1964.

Vanier, City of (1991)“Discussion Paper on Commercial Development in the City of Vanier” Prepared by the Department of Planning and Development, April.

↧

Update on 250 Montreal Road

(red) Location of the four-storey parking garage at corner of Levis and Begin; (green) Proposed buildings for Montreal Road; (yellow) Bus Loading Zone along Levis Ave (click image to enlarge)

Earlier this year, we commented on plans for a new development to be built at 250 Montreal Road, the new headquarters for the Association des enseignantes et des enseignants franco-ontariens (AEFO). Outlining revisions to those plans, a sign currently displayed at the location indicates that a four-storey parking garage is now being proposed for the rear of the project, This addition differs significantly from plans that were presented to the community in February – plans that included two levels of underground parking, an exterior green wall and a landscaped surface lot for 31 cars at the rear of the building. At the time (see our May 1 post), the developer and primary tenant (AEFO) were applauded by Councillor Fleury, local papers and community groups for an attractive design of an appropriate scale. In fact, the building was hailed as a flagship project for Montreal Road.

The cover of the promotional brochure for 250 Montreal Road, also called Place Vanier, makes no mention of the four-storey parking garage. Nor does the project’s website (click image to enlarge)

Commenting on the streetscapes and open space components of the original project proposal, the City of Ottawa’s Urban Design Review Panel highlighted the significance of the public spaces being created, commenting that “the urban condition in which this development is proposed is unique in that the building faces onto pedestrian environments on all four sides…. The proposed open space at the back of the project is fantastic.” The developer was encouraged to ensure pedestrian flow around the entire building – something noted in the draft plans.

The plans have since been changed with the removal of the landscaped surface-level parking lot and two levels of underground parking. These components have been replaced with a 57,000 square foot parking garage to be located at the corner of Begin and Levis. A treed pedestrian path, that was to connect Begin and Dupuis, has also been removed.

The entrance to the parking garage, which has space for up to 250 cars, is to be located immediately across from the new mural alongside the sidewalk in front of Assumption School, along Levis. The exhaust grille for the four-storey parkade is planned to face the school. The revised plan promises new trees along Begin and “pavers to match Montreal Road;” however, the drawings say little about the impact that the additional structure and car traffic may have on the adjacent neighbourhoods.

The need for sufficient parking spaces is realistic, as are the financial realities of an underground parking garage – costs that a developer needs to take into account when conceiving and presenting a project proposal. However, the decisions to allow a four-storey parking garage at the corner of Begin and Levis, which have the characteristics of residential streets, may be a mistake. The proposed plan could turn Begin into a long, unpleasant stretch interrupted only by a loading dock (where a pedestrian path to Dupuis was first planned). Furthermore, having an entrance to a 250-car parking garage directly across from a school and a Bus Loading Zone is arguably irresponsible.

Bus Loading Zone along Levis Avenue showing new mural. (click to enlarge)

Given that current zoning for the site allows for a parking garage, City of Ottawa planning staff have the delegated authority to approve the site plan amendment—though, comments from the community are currently being solicited. The AEFO garnered strong community support for its original plan, and the City of Ottawa now welcomes comments from residents on the revised site plan, as well. Information on how to submit comments regarding the new plan for 250 Montreal Road are available here. Comments are being welcomed until November 12. We’re interested in your reactions to the revised plan, too, and welcome your comments below.

(Mike Steinhauer)

↧

Vanier Snack Shack – Poutinized!

By Catherine Brunelle

(originally posted on bumpy boobs; October 25, 2012)

![]()

This evening, I ate a cheese-stringy, gravy covered, steaming hot bite of the neighbourhood at The Casse-Croute Vanier Snack-Shack. That’s right, we poutinized our evening and discovered another charming go-to destination amongst the streets of our new home. (And I watched a networking/marketing master at work – talk about having people invest in your business . . . oh my goodness, it was fantastic.)

Here’s the thing about Vanier that’s awesome, and what I never really anticipated before moving here. This area of Ottawa has a whole lot of community sunk right down deep into its streets, venues, and parks. And bit by bit – through the neighbours Zsolt gets chummy with, the fellow who bikes around with his trailer and waves hello, the dad who plays with his daughter every morning outside, the house that’s covered in ornaments, the park that hosts a spring-time sugar shack, and now our night excursion to the snack shack – we are learning more and more about this community.

I’m going to tell you about this Vanier Snack Shack right now, because I feel like it’s only right. You’ll see why in just a second.

Okay, this evening I had planned on baking salmon (still marinating and raw in the fridge at this moment) to eat along with the Naosap Harvest wild rice I was given at the Shesconnected conference this past weekend. Very healthy, no? Yes. But through a combination of feeling damn lazy, a wee bit discouraged from an unexpected bill (can you say, “whoops, I spent how much?!”), and being about a day away from my period – I was like, screw the salmon! I want to visit that remote snack house we noticed the other day by chance.

Zsolt wisely consented.

So we were off! Walking along the dark streets of the neighbourhood, we pass through an empty lot and approach the snack shack. Thankfully it’s open (we’ve tried to visit before and failed), which I can tell because there’s light coming from inside and there are little Christmas lights around the doorway and window.

In we go!

First impression: Inviting. There are little neon coloured poster boards all over and in different sizes advertising various food deals – two steamed hotdogs and small fries for 3 bucks, something called a bacon cheese hotdog, a variety of burger sizes, a poster for an American hotdog (?), an arrangement of styrofoam containers up on the wall with different prices, situated above a chest-high wooden counter, behind which is the kitchen, a fellow in an apron, a young lady looking on, and the owner – Serge.

And here’s why I think I have to write about this restaurant. (Not including the fact that Zsolt has labelled this his favourite poutine so far in Canada, citing the “harmonious mix” between the cheese, gravy and fries.) We were given such a warm welcome. Serge asked me firstly whether I was French, because I had a French sounding accent . . .I blame this on the word ‘poutine’, which I happen to say in a way that’s rather French. If ‘poutine’ and ‘croissant’ were the only two words I ever needed to say in French, I could be mistaken for a native speaker. . . anyhow, he then asked if we were new to the neighbourhood, advised us to buy property as Vanier is about to boom, talked with Zsolt about his new patent job & the office move, let us know there’s tons of art and music festivals in this area and we’re welcome to contribute if we have any ideas, and gave us a tour of his entire menu. All the while the young lady was trying to get our order, bue Serge wouldn’t stop telling us all about the area and his snack shack.

We did eventually get a big poutine. Not the biggest poutine, but a fairly large one nevertheless. Before leaving he gave us his card, and said he was looking into the facebook thing but never had any time for it. I’m not surprised. This fellow strikes me as sunk into his community and his restaurant. He’s organizing festivals, recruiting whoever walks through the door, and running what seems to me a successful small business. So no, he’s not online as of yet, but you can find ratings for the Vanier Snack Shack at www.urbanspoon.com– which he asked me to visit and rate, if I was so inclined.

So, are we going to go back? Duh. He made us feel like part of the community – he welcomed us to Vanier, and his long-waiting-customer-behind-us (apparently they are old friends) welcomed us to Vanier too; from now on, going to the Snack Shack will never just be about a harmonious poutine, it is about being part of the neighbourhood. (But of course, the yummy food also matters!) Brilliant welcoming – brilliant marketing – and just plain brilliant poutine.

Bonne Appetite! And yes, I am glad we moved to Vanier.

P.S. I loved the huge helping of cheese curds. If you have poutine without the curds, you are missing out!

(Photo by Catherine Brunelle, 2012)

(originally posted on bumpy boobs; October 25, 2012)

This evening, I ate a cheese-stringy, gravy covered, steaming hot bite of the neighbourhood at The Casse-Croute Vanier Snack-Shack. That’s right, we poutinized our evening and discovered another charming go-to destination amongst the streets of our new home. (And I watched a networking/marketing master at work – talk about having people invest in your business . . . oh my goodness, it was fantastic.)

Here’s the thing about Vanier that’s awesome, and what I never really anticipated before moving here. This area of Ottawa has a whole lot of community sunk right down deep into its streets, venues, and parks. And bit by bit – through the neighbours Zsolt gets chummy with, the fellow who bikes around with his trailer and waves hello, the dad who plays with his daughter every morning outside, the house that’s covered in ornaments, the park that hosts a spring-time sugar shack, and now our night excursion to the snack shack – we are learning more and more about this community.

I’m going to tell you about this Vanier Snack Shack right now, because I feel like it’s only right. You’ll see why in just a second.

Okay, this evening I had planned on baking salmon (still marinating and raw in the fridge at this moment) to eat along with the Naosap Harvest wild rice I was given at the Shesconnected conference this past weekend. Very healthy, no? Yes. But through a combination of feeling damn lazy, a wee bit discouraged from an unexpected bill (can you say, “whoops, I spent how much?!”), and being about a day away from my period – I was like, screw the salmon! I want to visit that remote snack house we noticed the other day by chance.

Zsolt wisely consented.

So we were off! Walking along the dark streets of the neighbourhood, we pass through an empty lot and approach the snack shack. Thankfully it’s open (we’ve tried to visit before and failed), which I can tell because there’s light coming from inside and there are little Christmas lights around the doorway and window.

In we go!

First impression: Inviting. There are little neon coloured poster boards all over and in different sizes advertising various food deals – two steamed hotdogs and small fries for 3 bucks, something called a bacon cheese hotdog, a variety of burger sizes, a poster for an American hotdog (?), an arrangement of styrofoam containers up on the wall with different prices, situated above a chest-high wooden counter, behind which is the kitchen, a fellow in an apron, a young lady looking on, and the owner – Serge.

And here’s why I think I have to write about this restaurant. (Not including the fact that Zsolt has labelled this his favourite poutine so far in Canada, citing the “harmonious mix” between the cheese, gravy and fries.) We were given such a warm welcome. Serge asked me firstly whether I was French, because I had a French sounding accent . . .I blame this on the word ‘poutine’, which I happen to say in a way that’s rather French. If ‘poutine’ and ‘croissant’ were the only two words I ever needed to say in French, I could be mistaken for a native speaker. . . anyhow, he then asked if we were new to the neighbourhood, advised us to buy property as Vanier is about to boom, talked with Zsolt about his new patent job & the office move, let us know there’s tons of art and music festivals in this area and we’re welcome to contribute if we have any ideas, and gave us a tour of his entire menu. All the while the young lady was trying to get our order, bue Serge wouldn’t stop telling us all about the area and his snack shack.

We did eventually get a big poutine. Not the biggest poutine, but a fairly large one nevertheless. Before leaving he gave us his card, and said he was looking into the facebook thing but never had any time for it. I’m not surprised. This fellow strikes me as sunk into his community and his restaurant. He’s organizing festivals, recruiting whoever walks through the door, and running what seems to me a successful small business. So no, he’s not online as of yet, but you can find ratings for the Vanier Snack Shack at www.urbanspoon.com– which he asked me to visit and rate, if I was so inclined.

So, are we going to go back? Duh. He made us feel like part of the community – he welcomed us to Vanier, and his long-waiting-customer-behind-us (apparently they are old friends) welcomed us to Vanier too; from now on, going to the Snack Shack will never just be about a harmonious poutine, it is about being part of the neighbourhood. (But of course, the yummy food also matters!) Brilliant welcoming – brilliant marketing – and just plain brilliant poutine.

Bonne Appetite! And yes, I am glad we moved to Vanier.

P.S. I loved the huge helping of cheese curds. If you have poutine without the curds, you are missing out!

(Photo by Catherine Brunelle, 2012)

↧

Church History

Writing any story about Vanier without making reference to one of the many churches that dot the landscape of this one square mile is a challenging effort at best. Interesting to note, however, is that the first church was not constructed until the end of the 19th century. Until then, the residents of Clandeboye and Janeville, two of the three villages that eventually made up Eastview (now Vanier), had to travel to Lowertown or Cyrville to attend church services. Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes (Vanier’s first church, see #1 on the map) opened in 1887 on the grounds of what was once Tara Hall—a brothel on Montreal Road. St. Margaret’s (#2), an Anglican church, opened further west in 1888 and St. Charles (#3), the second Catholic church, opened on Beechwood Avenue in 1908.

St. Margaret's Choir, early 1900's (Photo: McPhail family; Vanier Heritage Committee; City of Ottawa)

During the same year, in time for the 50th anniversary of the apparition of the Virgin Mary in Lourdes, France, Vanier’s own Lourdes Grotto was completed on the grounds of Notre-Dame.

The roots of Vanier’s protestant churches go back to the early 1900s when congregations met in halls on both Savard and Palace. In 1913, Eastview United (then Eastview Presbyterian Church; #4) opened their second church building on Olmstead, then selling the building to merge with Overbrook to form Eastbrook United Church in 1956. The site of Eastview Baptist (#5) was purchased in 1923 with the current building being completed a year later for a total of $21,000.

As the number of English-speaking parishioners at Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes grew larger, a petition was launched to establish Vanier’s first English Catholic church. Their efforts resulted in the 1931 establishment of Assumption Catholic Church, opened in what had been the vacant building on Savard left behind by Eastview Presbyterian. Assumption’s current building on Olmstead dates from 1940.

In an effort for Notre-Dame church to minimize the loss of French-speaking members due to the centrally located Assumption Church, Notre-Dame opened Marie-Médiatrice chapel in close vicinity of Assumption. The chapel, which opened in 1931, only offered services in French.

The late 1940s and 1950s were years of growth and prosperity for Vanier. As housing developments were constructed, so grew the church communities (See Blake Boulevard post). By the 1950s, St. Charles had grown beyond its capacity and Notre-Dame-du-Saint-Esprit (#7) was established to handle the overflow. Located on Carillon, this modern church building opened in 1958 – and opened amidst some controversy. The large sculpture of Mary that adorned the outside façade depicted the Virgin with bare feet. The sculpture was created by Raoul Hunter, a Quebec artist who was also responsible for the magnificent Mackenzie King sculpture on Parliament Hill.

Exterior of Notre-Dame-du-Saint-Esprit, now Vanier Community Church (Photo: VanierNow, 2012)

Two years later, the Marie-Médiatrice Church (#8) moved into their modern edifice on Cyr Avenue. The nomination of a female vicar, Sister Reine Barrette, (also) caused some controversy.

The forward looking lines (and avant-garde style) of the Marie-Médiatrice Church, however, stand in stark contrast to declining attendance patterns. Reflecting Vanier’s broader demographic shifts, by 1960, the number of baptisms at both Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes and St. Charles declined while the number of funerals rose. Families started to leave Vanier for newer and more comfortable homes in the suburbs and broader societal changes started to have significant impacts on church life:

“French-Canadian society before 1960, is impregnated with religion and, at times, with religiosity. However, with the Quiet Revolution, the secularization of society, the Second Vatican Council and liturgical changes, churches are less and less frequented by the faithful” (Laporte, 204).

Yet it was an event in 1973 that had perhaps the most devastating impact on Vanier’s church community. Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes, Vanier’s oldest church, was destroyed by fire when on May 28 a massive blaze engulfed the soaring building in the middle of the night. Following the destruction and the assessment of the damage, the congregation was determined to reconstruct on Montreal Road.

Notre-Dame re-opened the doors to its new (and very modern) building for midnight mass on Christmas Eve, 1975. The church’s iconic tower, incorporating the original bells saved from the fire, was completed in 1987.

Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church (Photo: VanierNow, 2011)

Notre-Dame-du-Saint-Esprit never experienced the growth of its sister churches. In fact, attendance started to decrease by the mid 1960s, and the church closed in 1995. The building stood empty for several years until City Church (now the Vanier Community Church) began operating in the facility in 2000. The Bikers Church has been meeting in the same halls since 2010. The two churches merged (while keeping their separate services) in 2012.

Eastview Baptist and St. Margaret’s have also witnessed shifts in attendance. Both churches still offer services in English; however, the former now offers a service in Portuguese while the latter conducts its 11:00 am service in both English and Inuktitut. Also, since 2008, St. Margaret’s has been sharing the building with The Village, a Mennonite church.

As the population of Vanier continues to shift and religious and spiritual practices broaden, the use of these important edifices may change (again). In 2010, a mere two years after its centenary, St. Charles church closed its doors. While it is unlikely that another congregation will move into this space, the building itself is the memory of a congregation and that of an entire community. Depending on its future occupant and use of the site, St. Charles, like St. Brigid’s Church in Lowertown, could once again become a pillar in Vanier and in the broader community.

(Mike Steinhauer)

Cursory timeline of Vanier’s church history:

1887 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes (Vanier’s first church) opens on Montreal Road

1888 St. Margaret's Anglican Church opens on Montreal Road

1908 St. Charles Church opens on Beechwood Avenue

1908 Grotte de Notre-Dame de Lourdes is completed

1913 Bell tower of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes is completed

1913 Eastview Prespetyran Church (later Eastview United Church) opens on Olmstead

1924 Eastview Baptist Church opens on Olmstead

1931 Assumption Church opens in the former Eastview Prespetyran Church hall on Savard

1931 Marie Médiatrice Chapel opens on Cyr Avenue

1940 Assumption Church constructs its new building on Olmstead

1958 Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit Church opens on Carillon Street

1960 Marie Médiatrice Church constructs its new building on Cyr Avenue

1973 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church is destroyed by fire

1975 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church reopens in its new building

1987 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church’s new bell tower is completed

1995 Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit Church closes

2000 City Church is established in the former space of Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit

2008 The Village Church opens (sharing space with St. Margaret's Anglican Church)

2010 St. Charles Church closes

2010 Biker’s Church (established in 2002) moves into City Church

2012 City Church and Biker's Church merge to form Vanier Community Church

Sources:

Association des citoyens de Vanier. La petite histoire de Vanier. Vanier: O.V.U.L, 1975.

Brockwell, Tara. “Vanier Church Celebrates Leather, Bikes and Jesus Christ.” Open File Ottawa. May 23, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2012. (LINK)

Deschamps, Eric R. “Get the Water Flowing; Restoring Our Community’s Rich Heritage.” (unpublished sermon notes) July 29, 2000.

Eastview Baptist Church. “Our Story.” (n.d.) Accessed November 3, 2012. (LINK)

Hunter, Raoul. “Sculptures.” Sculptor and cartoonist. (n.d.) Accessed November 3, 2012. (LINK)

Kavcic, Patty. “Eastbrook United Church.” (unpublished; n.d.) (LINK)

Laporte, Luc. Vanier. Ottawa: Centre franco-ontarien de resources pédagogiques, 1983.

Cursory timeline of Vanier’s church history:

1887 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes (Vanier’s first church) opens on Montreal Road

1888 St. Margaret's Anglican Church opens on Montreal Road

1908 St. Charles Church opens on Beechwood Avenue

1908 Grotte de Notre-Dame de Lourdes is completed

1913 Bell tower of Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes is completed

1913 Eastview Prespetyran Church (later Eastview United Church) opens on Olmstead

1924 Eastview Baptist Church opens on Olmstead

1931 Assumption Church opens in the former Eastview Prespetyran Church hall on Savard

1931 Marie Médiatrice Chapel opens on Cyr Avenue

1940 Assumption Church constructs its new building on Olmstead

1958 Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit Church opens on Carillon Street

1960 Marie Médiatrice Church constructs its new building on Cyr Avenue

1973 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church is destroyed by fire

1975 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church reopens in its new building

1987 Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes Church’s new bell tower is completed

1995 Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit Church closes

2000 City Church is established in the former space of Notre-Dame du Saint-Esprit

2008 The Village Church opens (sharing space with St. Margaret's Anglican Church)

2010 St. Charles Church closes

2010 Biker’s Church (established in 2002) moves into City Church

2012 City Church and Biker's Church merge to form Vanier Community Church

Sources:

Association des citoyens de Vanier. La petite histoire de Vanier. Vanier: O.V.U.L, 1975.

Brockwell, Tara. “Vanier Church Celebrates Leather, Bikes and Jesus Christ.” Open File Ottawa. May 23, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2012. (LINK)

Deschamps, Eric R. “Get the Water Flowing; Restoring Our Community’s Rich Heritage.” (unpublished sermon notes) July 29, 2000.

Eastview Baptist Church. “Our Story.” (n.d.) Accessed November 3, 2012. (LINK)

Hunter, Raoul. “Sculptures.” Sculptor and cartoonist. (n.d.) Accessed November 3, 2012. (LINK)

Kavcic, Patty. “Eastbrook United Church.” (unpublished; n.d.) (LINK)

Laporte, Luc. Vanier. Ottawa: Centre franco-ontarien de resources pédagogiques, 1983.

↧

↧

Notre-Dame Cemetery: New website commemorates one of Ottawa’s most historic cemeteries

VanierNow is pleased to introduce a new website devoted exclusively to Notre-Dame Cemetery—the largest Catholic cemetery in the Ottawa-Gatineau region. In collaboration with Jean Yves Pelletier, a local historian and author, the site presents a historical overview of the cemetery, lists over 100 prominent figures and features a photographic account of what is one of Ottawa’s most beautiful and most historic cemeteries. Notre-Dame Cemetery, located on the eastern edge of Vanier, is the final resting place of more than 130,000 individuals, including Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, renowned portrait photographer Yousuf Karsh and former Vanier (then Eastview) mayor Donat Grandmaître.

The new bilingual website, the first of its kind, can be accessed directly by visiting www.NotreDameOttawa.ca

Photo Credits

Top: Monument of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (Mike Steinhauer); Detail of a tomb (Alexis Loriot); Scott D'Arcy (City of Ottawa Archives; CA-1933)

Middle: Field of Honour (MS); Entrance to cemetery (Library and Archives Canada; PA-043835)

Bottom: Jean Dallaire (National Gallery of Canada); Suzanne Cloutier (Cover of Mon Film magazine); Mausoleum of Rivet family (MS); Self-portrait by KarshYousuf (Library and Archives Canada; PA-212511)

The new bilingual website, the first of its kind, can be accessed directly by visiting www.NotreDameOttawa.ca

Photo Credits

Top: Monument of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (Mike Steinhauer); Detail of a tomb (Alexis Loriot); Scott D'Arcy (City of Ottawa Archives; CA-1933)

Middle: Field of Honour (MS); Entrance to cemetery (Library and Archives Canada; PA-043835)

Bottom: Jean Dallaire (National Gallery of Canada); Suzanne Cloutier (Cover of Mon Film magazine); Mausoleum of Rivet family (MS); Self-portrait by KarshYousuf (Library and Archives Canada; PA-212511)

↧

Vanier Remixed

Imagine St Charles Square become (once again) our community hub, with French-Canadian music and dancing giving way to the contemporary beats of DJs, break dance, slam poetry and Les Mosquitos– while audio-video projections and sounds infuse the site with visuals, music and energy. With a photography installation recalling both historic and modern Vanier, and with food, arts and activities, the site again becomes alive.

Great urban spaces are (often) borne out of the re-appropriation and re-imagination of public spaces – opportunities for residents and visitors alike to experience places in new ways. Vanier’s public spaces, like St Charles Square, are set to be reshaped and reclaimed as C’est Chill, an early winter arts and culture festival, takes to our streets and parks on December 1. The event welcomes individuals to “Vanier’s renaissance,” and the day’s events – steeped in Vanier’s own traditions – are set to bring a contemporary edge to Vanier.

Artistic Director and musician Dominique Saint-Pierre, having recently co-created with video artist Shaun Elie a river-inspired soundscape for Nuit Blanche (beautifully situated under the downtown Plaza Bridge), has assembled a program that celebrates Vanier’s unique heritage, its urban landscape, and its contemporary diversity.

The event kicks off at noon with the calling of church bells across the neighbourhood. Then imagine a parade. Led by Junkyard Symphony, and bringing together First Nations drummers, cyclists, noisemakers and groups in-between, the march departs Place Dupuis on Montreal Road, follows Vanier’s traditional architecture (and decorative houses) of Marier Street, to Beechwood and St Charles Square, once the active front lawn of St Charles parish.

Near the Rideau River, at the corner of Beechwood and the Vanier Parkway,Aboriginal artists are set to install a massive neighbourhood dream-catcher to capture the community’s hope and aspiration. Imagine, too, community-sourced public art, with a mural taking shape and giving life to the too-persistent wooden boarding around the Beechwood fire site. And imagine (even still) the softening of lamp posts and street lights on many of Vanier’s commercial main streets. All month, led by artists Mélanie Gatt and Amaury Lavoine, community members are knitting and crocheting, preparing to yarn bomb Vanier with cozy and colourful coverings.

Perhaps the beauty of C’est Chill lies in its fusion of that which frustrates with that which inspires, bringing together old and new in a celebration of community and public space. It’s Vanier remixed. Welcome to the renaissance.

Image Credits: Dream Catcher (Pinkyboon); Architectural Foundation (Mike Steinhauer); Notre Dame Bells (VanierNow); A display in Yellow Springs (Shrewdcat); Renaissance Logo (C'est Chill Event Poster; Vanier BIA)

Artistic Director and musician Dominique Saint-Pierre, having recently co-created with video artist Shaun Elie a river-inspired soundscape for Nuit Blanche (beautifully situated under the downtown Plaza Bridge), has assembled a program that celebrates Vanier’s unique heritage, its urban landscape, and its contemporary diversity.

The event kicks off at noon with the calling of church bells across the neighbourhood. Then imagine a parade. Led by Junkyard Symphony, and bringing together First Nations drummers, cyclists, noisemakers and groups in-between, the march departs Place Dupuis on Montreal Road, follows Vanier’s traditional architecture (and decorative houses) of Marier Street, to Beechwood and St Charles Square, once the active front lawn of St Charles parish.

Near the Rideau River, at the corner of Beechwood and the Vanier Parkway,Aboriginal artists are set to install a massive neighbourhood dream-catcher to capture the community’s hope and aspiration. Imagine, too, community-sourced public art, with a mural taking shape and giving life to the too-persistent wooden boarding around the Beechwood fire site. And imagine (even still) the softening of lamp posts and street lights on many of Vanier’s commercial main streets. All month, led by artists Mélanie Gatt and Amaury Lavoine, community members are knitting and crocheting, preparing to yarn bomb Vanier with cozy and colourful coverings.

Perhaps the beauty of C’est Chill lies in its fusion of that which frustrates with that which inspires, bringing together old and new in a celebration of community and public space. It’s Vanier remixed. Welcome to the renaissance.

Image Credits: Dream Catcher (Pinkyboon); Architectural Foundation (Mike Steinhauer); Notre Dame Bells (VanierNow); A display in Yellow Springs (Shrewdcat); Renaissance Logo (C'est Chill Event Poster; Vanier BIA)

↧

Vanier Walk-ups (teaser #1): Two weeks 'til launch

↧

Place Vanier (teaser #2): Ten days 'til launch

(Photo: VanierNow 2012)

↧

↧

Gamman House reborn: Vanier’s bellwether property?

Gamman House (Photo & Design: VanierNow 2012; Floor Plan: City of Ottawa)

What could it mean to create spaces for culture? Transforming existing under-used or unused spaces – particularly those in City-owned properties – into accessible spaces for diverse and emerging artists is one recommendation in the City of Ottawa’s freshly minted Renewed Action Plan for Arts, Heritage and Culture in Ottawa (2013-2018), passed earlier this year. In Vanier, we’re about to see that idea brought to life with the 2013 opening of artist studios in Gamman House, one of two designated heritage properties in Vanier, located at 306 Cyr Avenue.

With its diversity, heritage, proximity to downtown – and affordability – there may be little surprise in witnessing what has been referred to Vanier’s cultural renaissance. At a Community Forum in early November, City staff spoke of exciting findings in a cultural mapping of the neighbourhood – and stories of the arts infusing Vanier are increasingly common. While looking ahead to C’est Chill, a one-day festival on December 1, one might also look back to Beechwood’s first Art in the Parking Lot, held in June. Currently, the International Digital Miniprint Exhibition 7 continues at Voix Visuelle (81 Beechwood), while affordable space led Ottawa’s own The Gallop to record its first release right here, earlier this year.

Scheduled to become home to studio space in 2013, Gamman House will again become a positive addition to the mix. The small City-owned wood-frame cottage-style property on Cyr Avenue was designated under the Ontario Heritage Act in 2004 as a property of cultural heritage significance. While having been empty for several years, the property was home in the 1990s to Club 60 de Vanier, the forerunner to Centre Pauline-Charron, and was then briefly occupied by the Ottawa Worker’s Heritage Centre beginning in 2004. This Victorian-style workers’ house itself is an important part of Vanier – both for its architecture, and its history. Built by Nathaniel Gamman between 1874-1875, the house is celebrated for its mansard roof, wood siding and decorative wood features. Dating back to the founding of Janeville, the house also reflects the development of a working class community along Montreal Road – part of Vanier’s early evolution.

Preserving this heritage, while becoming artist studio space, the house is about to link to another thread in Vanier’s evolution. The property was re-zoned in 2011 to allow for the City’s creation of an artist’s facility – and will become the newest of three locations for the City’s Artist Studio Program (ASP), providing private studios for individual artists. One short-term studio space will be available for use by First Nations, Inuit and Métis artists (up to two six-month occupancies per year), while three long-term studio spaces will become available for three-year studio rental agreements. With possible exhibition space and an annual open house for the public, the space will also create new opportunities to engage with one another. Artists, to be selected through a Call for Artists (closing November 23) and decided by a peer jury process, are expected to notified in late December. Soon after, the artists themselves will fill these -- Vanier's newest -- spaces for culture.

(Mike Bulthuis)

↧

Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes (teaser #3): Five days 'til launch

(Photo: VanierNow 2012)

↧

Vanier Sugar Bush (teaser #4): One day 'til launch

↧

.jpg)

,+159+Montreal+Road.jpg)

.jpg)

,+Beechwood+Avenue;+by+architect+Charles+Brodeur.jpg)

;+by+architect+Francis+Conroy+Sullivan.jpg)

.jpg)

+and+statue+of+Our+Lady+of+Africa+(1955),+part+of+the+former+White+Fathers%E2%80%99+seminary+(now+Richelieu+Park).jpg)

,+155+Carillon+Street+.jpg)

,+160+Duford+Street+.jpg)

,+by+Douglas+Cardinal+and+Cardinal+Conley+&+Associates.jpg)